The big bang of civilisations: the keys to human progress

Summary:

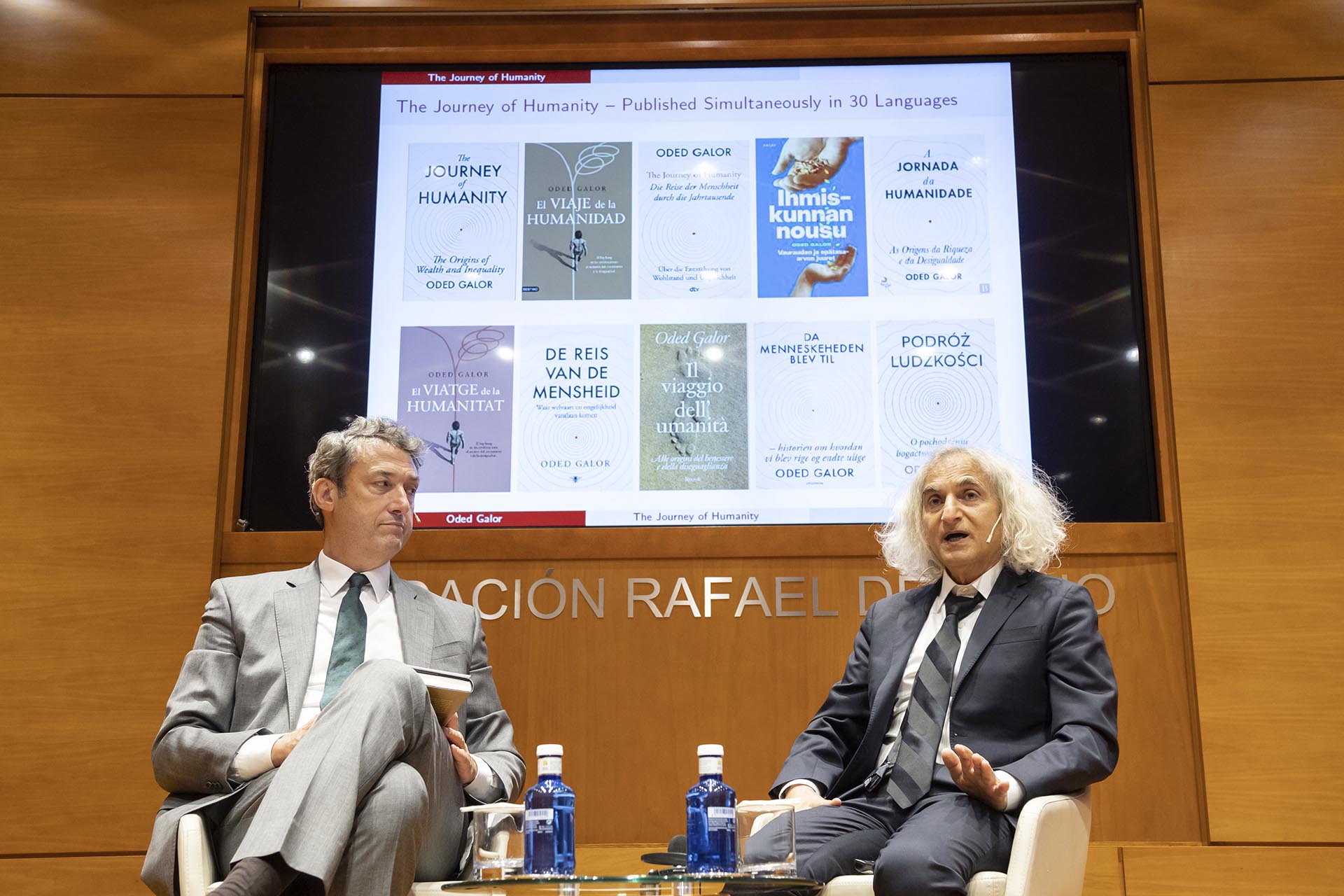

On 19 July 2022, the Rafael del Pino Foundation organised the conference "The big bang of civilisations: the keys to human progress", given by Oded Galor, Professor of Economics at Brown University, on the occasion of the publication of his book "The Journey of Humanity".

According to Galor, there are two fundamental mysteries to be unravelled. The first is the mystery of growth: what are the roots of the dramatic transformation in living standards that has taken place in recent centuries, after hundreds of thousands of years of stagnation? Then there is the mystery of inequality, what is its origin.

Throughout history, life was nasty, brutish and short. It was much like that of other species, focused on survival and reproduction, and living conditions across the planet were much the same in all places over time. 25% of the newborns did not live to be a year old and half of them did not reproduce. Many women died in childbirth. And life expectancy ranged from 25 to 40 years. An economic crisis led to famine and extinction.

In the last two hundred years we see a fantastic improvement in living standards across the globe. Per capita income in the world is growing by a factor of fourteen. Life expectancy has doubled. But there is a great divergence in living conditions over time and space.

To understand this metamorphosis, let us think of the inhabitants of Jerusalem at the time of Jesus Christ and bring them into the 19th century. These people will be able to adjust instantly to the 19th century because the knowledge of the past is still viable. Technological improvements are only incremental and will allow instant adaptation. The jobs will require very similar skills. And, above all, life expectancy has not changed. There is no need to rethink the human mentality.

If we take these people to 21st century Jerusalem, they are going to be shocked because past knowledge is outdated. Modern technology is going to look like magic. Jobs require incomprehensible knowledge. And life expectancy has doubled and forces us to think about the future, to make decisions about education, savings, investments, in a completely different life cycle than in the past. So something has happened in two hundred years that has never happened before in the evolution of human beings.

These levels have not grown incrementally throughout man's presence on Earth. Throughout 99% of human history on the planet, there is no change in the standard of living. What we do see is a technological improvement, which is gradual. But this technological progress does not affect the well-being of the population, only its size. The fourteen-fold increase in per capita income in the world reflects an abrupt transformation when the tipping point is reached.

To conceptualise this change, let's think about the evolution of per capita income over the last two thousand years. There is practically no change until the advent of the industrial revolution, which is when it skyrocketed in the last two centuries.

Per capita income is maintained by Malthusian forces over time and then shoots up like an arrow in the last two hundred years. This take-off does not happen all over the world at the same time. Some societies take off in the 18th century and others take longer, resulting in tremendous divergence between countries. Societies that take off first multiply their per capita income, and others lag behind, resulting in tremendous divergence. This implies that much of the inequality in the world originated two centuries ago. So if we want to understand inequality today, we have to investigate those forces that were present in the past.

The solution to these mysteries is very important. It requires identifying the forces that allow the transition from stagnation to growth, the forces that explain the origin of divergence, and the role that some historical and prehistoric forces play in the evolution of different societies. Solving these mysteries is crucial if we are to alleviate these inequalities. We need to better understand these forces that give rise to this divergence. We need to better understand humanity's journey, how humanity progresses over time.

We can divide the development process into three fundamental stages. The first is what we can call Malthusian, the second is post-Malthusian and the third is modern growth. The first begins three hundred thousand years ago in Africa, when an anatomically modern human being appears. It is characterised by stagnation and dynamism. This dynamism allows the world to advance and reach the post-Malthusian stage. In this stage, Malthusian forces prevent per capita income from advancing without a population counter-balance. The demographic transition in Western Europe in 1870 frees this process from the population counter-balance and allows the world to advance and reach this regime.

If we want to understand inequality in the world, we have to understand what these forces of the Malthusian era were. There is a very interesting dualism, the stagnation of living standards and life expectancy, which goes hand in hand with dynamism in the context of technology, population growth and human adaptation. Technological progress, population growth and adaptation are very slow. But in a period of three hundred thousand years since the emergence of mankind, this represents a tremendous variation. It is this Malthusian dynamism that ultimately illuminates the transition from stagnation to growth.

It is critical to understand what these wheels of change look like. There are three, technological progress, population scale and human adaptation. When technology evolves during the Malthusian era, it leads to a temporary increase in per capita income, but it lasts for a long time because the population grows as more children are born and survive. Consequently, per capita income declines. In other words, there is a temporary increase, but as the population grows, per capita income returns to its previous level.

This gives rise to powerful predictions that can be tested. This implies that technologically advanced societies, or those rich in land, were not richer. They were simply more densely populated. If we study the relationship between productivity, or ferocity, population and population density in the Middle Ages, more productive societies have more population. But there is no relationship between productivity and per capita income. Those societies will be more densely populated, but they will not be richer. The same is true of technological progress. Technological progress translates into more population, not richer people. This is critical if we are to understand the transition from stagnation to growth and, secondly, the mystery of inequality.

The second element that is also very important is the impact of technological progress on human adaptation, basically on cultural adaptation. This Malthusian pressure affects the size of the population, but also its composition, that is, the type of trait that is being selected, be it cultural or individuals that are complementary to technological progress. These individuals generate higher levels of income, but in the Malthusian epoch this is converted into higher reproductive success. This, in turn, results in these traits becoming increasingly prevalent in the population. In the Malthusian epoch, adaptation occurs, increasing the prevalence of these traits and leading to the transition from stagnation to growth.

The third element has to do with the origin of technological progress. This progress is not manna that falls from the sky, but is affected by the size of the population and its adaptation. If the size is larger, there will be more innovators, so technology will advance faster, there will be more demand for innovation, incentives will be higher, there will be a greater dissemination of knowledge, it will lead to the division of labour that will increase commercial activities and, therefore, there will be greater technological developments. The size and composition of the human population affect technological progress. Technological progress, in turn, will affect the size and composition of the population.

This is important because it is a positive loop, which feeds back in a positive way. The population supports more technological progress, which supports more population, which in turn supports more technological progress. This is a reinforcing iteration that leads to technological acceleration on the scale that we see in the industrial revolution.

It is so important because when technological progress occurs, human capital becomes essential for human beings to cope with this changing technological environment. But people are poor, they can't afford to educate their children if they don't save for other expenses. Consumption is subsistence. Therefore, they have to save on the number of children, which leads to a decline in fertility, the so-called demographic transition. This decline frees the population from the Malthusian imbalance, which disappears, because in order to invest in human capital one has to save on the number of children. Thus, technological progress, human capital improvement and population decline lead to sustained economic growth.

Humanity began in Africa three hundred thousand years ago. The population size is very modest. Despite this, there is one very important advantage of humans, which is the brain, which allows technology to advance. The technological frontier moves slowly but steadily. These wheels of change reinforce each other. The size of the human population increases dramatically in these three hundred thousand years, with the agricultural revolution and the industrial revolution. Technological progress accelerates and we move from stone tools to the steam engine. Suddenly, the technological landscape changes very rapidly and people start investing in the education of their children so that they can adapt. Once this change occurs, the demographic transition takes place and the world moves towards sustainable growth.

Think of this transition as the transition from liquid to gas when heating water. When you light the fire, you don't see much change in the nature of the water. But when it reaches a hundred degrees Celsius, we see the process of evaporation and the change from liquid to gas phase. The same thing happens in the course of human history. The societies of the Neolithic revolution are agricultural societies. In this period, we see technological progress advancing faster and faster, but we do not see any change in the welfare of the population because its growth counteracts the impact of technological change. But there comes a time when technological progress induces investment in human capital, leads to fertility decline and the Malthusian trap is broken. The phase change we see in this context is based on the idea that there is a qualitative change in the nature of the system and we move to the economy of the modern world.

If you think about water and the evaporation process, you will have noticed that some molecules evaporate before others. As a result, there is an inequality between water molecules: some are in the gas phase and others are in the liquid phase. The same can be said of the world economy: some societies take off earlier and others remain in Malthusian equilibrium, and a huge and growing gap emerges. Those molecules that are going from liquid to gas earlier have to do with random elements, but, above all, with the location of the molecules in the kettle. The same can be said of human history. Geographical evolution affects when societies take off and the inequality we see in the world.

Today's inequality originated, above all, in differential take-off, which originates in forces that began to operate thousands of years ago. So when we think of inequalities, it is very tempting to think of differences between countries in human capital, in education, in the use of capital, in technological levels. But this leads us nowhere, but to the question, if this is the case, why some societies have not invested in physical and human capital and adapted advanced technologies. This brings us to the important question of what are those barriers that prevent some societies from participating in this process of technological accumulation.

This brings us to factors rooted far back in time. They are cultural, institutional characteristics. But these different characteristics are based on economic development, on the ultimate forces: geographical forces and the characteristics of societies. To try to understand these inequalities today I go backwards and look at colonialism, institutions, geography, all the way back to the departure of human beings from Africa and its impact on human inequality.

Many propose that institutions are critical forces in the inequality we see in different parts of the world, where different institutions emerge in different societies. Some societies adopt inclusive institutions that generate growth; others adopt extractive institutions that hold it back, which would explain the inequality we see in the world today. Now, from time to time, institutions emerge out of nowhere, randomly at a critical juncture, but the differences are very small. The Black Death created a labour shortage which led to an increase in the demand for labour. As a result, feudalism was disappearing in England, which led to the emergence of property rights. Some authors argue that this is what led to the emergence of the industrial revolution in England. Another important example is the Glorious Revolution, or Revolution of 1688, which leads to the birth of a constitutional monarchy in England and the establishment of property rights and, again, the beginnings of the industrial revolution. We can think of a counterfactual history where William of Orange was defeated by James II. The industrial revolution would not have happened, there would have been an absolute monarchy and industrialisation would have taken place elsewhere in the world. The final, and most curious, is the division of the Korean peninsula along the 38th parallel, which leads to a huge gap in per capita income between North and South Korea. In South Korea, per capita income is 24 times higher than in the North and life expectancy is eleven years longer. If we consider a counterfactual story, in which the South would not be the locus of influence of capitalism, but the North. Then we would see a reversal in this pattern. But in general, the number of cases where institutions emerge randomly at critical junctures is very small.

Institutions gradually evolve with the development process and adapt to the technological and geographical environment. The agricultural revolution leads to higher population density and the formation of cities and states. Consequently, it generates a demand for institutions that can enable cooperation between individuals, establish property rights and allow for the provision of public goods.

Ecological diversity is associated with more trade and, at the same time, with early state formation and, consequently, with the demand and supply of institutions. Another critical factor is the suitability of the soil for large plantations. In some regions, crops can be grown that are good for large estates. This generates a concentration of land, increases the power of its owners and allows the establishment of extractive institutions and the terrible institution of slavery. If we think of an environment of disease, with low population density, the creation of centralised political institutions is delayed. To some extent, once again geography is behind different institutions in the world. If we want to understand institutions in the world, we will have to understand these critical junctures that give rise to the differential development of institutions, but we will also have to look for deeper forces and societal characteristics.

This brings us to the cultural factor. If we think about cultural characteristics, we see that different types emerge. Some societies adopt characteristics that generate growth, such as social capital, and others adopt those that retard growth, such as cultural ties, as in the case of southern Italy. There we see the adoption of family circles, which are very strong and avoid transactions outside the family, which is detrimental. In Northern Italy, on the other hand, we see the emergence of social capital in the form of widespread trust and civic participation.

There are some examples of random cultural mutations in history. For example, the imposition of compulsory literacy in Judaism in the 1st century. This resulted in the persistence of the predisposition towards education. The decree, initially, was not related to economic welfare, but was linked to religion. This bias towards education was maintained over time. A second example is the emphasis on thrift and entrepreneurship in the Protestant world. For many, this is associated with the spirit of capitalism. So there are some cases that give rise to cultural characteristics, but they are very rare. In most cases, the culture is adapted to the geographical environment.

If we think about this process, culture evolved and adapted to the environment. When there was an increase in education, there was a gradual change in society's predisposition towards it. Parents are more inclined to invest in the quality of their children. Rather than quantity, they prefer more quality, more educated children. The suitability of the soil for ploughing led to the introduction of the plough, but because it requires strength of body, it led to the division of labour by gender. Or if we think of climatic volatility, it affected the degree of loss aversion and thus the level of entrepreneurship. Finally, if you think about crop yields, some societies have very productive crops and others do not. If you have good crops, you can engage in the process of planting and harvesting. This gives rise to behaviour that focuses on the future. People plan for it. This is associated with a more future orientation.

How much crop can we extract from the soil? In Southeast Asia, the soil is of higher quality. In Europe as well. This contributed a lot to a behaviour that focuses on the future, to think about the future, to plan for the future, which is a very important feature of the growth process because technology adoption and education and investment decisions depend on it.

Cultural forces are important, but they are associated with these deeper forces, which are geographical and societal. This brings us to what we call the shadow of geography. Geographic features such as soil quality, the environment of disease and isolation, and the impact on the emergence of cultural and institutional features that are important for economic growth. Geographic characteristics have a direct impact on economic development. A disease environment affects labour productivity and capital accumulation, and if we are in an environment of isolation, this will affect technological progress and isolation. The long shadow of history works through the effect of geography on institutional and cultural characteristics.

The concern with cultural characteristics takes us back 12,000 years to the agricultural revolution, where we see the transition from hunter-gatherer tribal societies to more sedentary agricultural societies. This is associated with increased food production and the emergence of a non-food producing class. That is, individuals who can devote their time to creating knowledge in the form of science, technology and writing. The moment we participate in them we generate new technologies that result in technological advancement that provides advantages over other societies. Jared Diamond suggests that much of today's inequality can be traced back to these variations in societies that predate the Neolithic era, which had a technological advantage that still persists. The evidence, however, is conflicting, because the passage to the neolithic revolution is very important for understanding comparative development in the Middle Ages, but it is totally irrelevant for understanding comparative development today. Inequality today cannot be explained by the beginning of the neolithic revolution.

The societies that started the neolithic revolution earlier are not necessarily the societies that dominate the world today. The neolithic revolution in Europe occurred earlier in the south than in the north, but the north dominates the south economically. The same is true of China and Middle Eastern societies, which are not dominating the world either. What happened is that, in the course of globalisation, societies that had a comparative advantage in agriculture became locked into agriculture. And because this activity has no secondary or spillover effects on other issues, societies that did not have to create food were able to move on to other things and move forward.

This brings us to Africa. Humans left there between sixty and ninety thousand years ago and began to populate the world. This affects the distribution of population and diversity in the world and has an effect on comparative development. During this exodus, the migrating populations brought with them a subset of the cultural diversity that existed in Africa, which can be cultural, phenotypic, linguistic and cultural.

Migration is sequential. Consequently, the further away from Africa they go, the lower the level of diversity these populations will have. Think of the population in East Africa, which was more diverse. This population starts to migrate, but they did not carry the enormous diversity that existed among the African population because they were modest in size and the population that migrated was small, so they were not representative of the population that existed in Africa. The new population that emerges in the Middle East is therefore less diverse than the population that was in Africa. People live there for many years and at a certain point they migrate again because the territory cannot support such a large population. They migrate to Europe forty-five thousand years ago and, again, they bring a subset of the diversity that existed in the Middle East. Some go east and cross the Bering Strait to America forty-five thousand years ago and arrive in South America forty thousand years ago. The further they migrate, the less diverse that population is.

Empirical evidence shows that the further we move away from Africa, the less diverse the population becomes. This is true no matter how we look at diversity. Why does it matter? It is critical to understanding current inequalities. These events that occurred sixty or ninety thousand years ago are still persisting. This is important because diversity has benefits on creativity and innovations, as it is associated with a cross-fertilisation of ideas and complementarities in the production process. The more diverse a society is, the more innovative it is.

On the other hand, diversity is associated with a lack of cohesion. The more diverse a society is, the less cohesive it is. This results in a lack of trust, disagreement over desirable public goods and thus more conflict. If there are positive and decreasing effects, then we would expect an inverted U-shaped relationship between diversity and prosperity, which is associated with prosperity. The evidence, in fact, is striking. In the 1500s, the societies that were optimal in terms of diversity were China, Korea and Japan. These are societies that we do not normally associate with an optimal level of diversity. But this is a time when technological progress is not very important, so the effects of cohesion are much more important than the possible adverse effects on innovative capacity. As we move into the modern world and technological development, optimal diversity is associated with the level of diversity in the United States. As time goes by, it seems that diverse societies have the upper hand, but if we think about societies that are going to become more and more technologically advanced in the future, this cultural fluidity is going to become more and more important and diversity is going to be essential to cope with these rapidly changing technologies. This relationship can be observed in all countries.

What is important is that the wheels of change are turning, but not in a vacuum. They are affected by institutions, culture and geography, but also by human diversity. Thus, more diverse societies produce more technological progress than others. This gearing, these wheels, also move faster. Societies with better institutions have more technological progress because intellectual property rights are protected. They are societies with a greater propensity to education, with lower fertility rates and, therefore, changes in the composition of the population give rise to technological progress. This machinery of change moves at different speeds in different parts of the world. So, when we come to the beginning of the 19th century, some societies are overcoming these great changes, this technological progress that allows this stagnation of growth to take off. But other societies are moving more slowly. So their transition is delayed.

If we think about the origins of comparative development, 86% of the variations in inequalities today can be traced back to historical roots. Between 17% and 26% it has to do with the dispersal of anatomically modern humans from Africa. The time since sedentary societies and the Neolithic revolution accounts for approximately 3%. Geo-climatic factors, approximately 30%. Disease environment, 10%. Cultural factors, approximately 20%. And institutions, between 3% and 9%.

If we now want to mitigate inequality in the world, we will have to better understand what these forces are. Humanity's journey allows us to understand that history is not our destiny, and that if we understand history, we will be in a better position to design a better future. Policies for inclusive growth-enhancing institutions are extremely important because they will have to be specific to a country, a history, a geography. One policy does not fit all countries at once. If we want to mitigate the cost of diversity and enhance the benefits, the advantages of diversity, in diversified societies education must focus on promoting social cohesion and tolerance. But if we are talking about homogenous societies, it must promote the ability to think differently, to generate pluralism. In agricultural societies, we need to devote more resources to promoting forward-looking approaches. When we think about progressive policies, we tend to implement them because we think they are good values. We must take on these policies for the sake of efficiency. We should talk about gender equality, which is critical for fertility decline; we can talk about tolerance, which can reduce the effects of diversity, and it can be pluralism, which is going to lead to an exchange of ideas so that societies take advantage of these diversities.

The Rafael del Pino Foundation is not responsible for the comments, opinions or statements made by the people who participate in its activities and which are expressed as a result of their inalienable right to freedom of expression and under their sole responsibility. The contents included in the summary of this conference are the result of the debates held at the meeting held for this purpose at the Foundation and are the responsibility of their authors.

The Rafael del Pino Foundation is not responsible for any comments, opinions or statements made by third parties. In this respect, the FRP is not obliged to monitor the views expressed by such third parties who participate in its activities and which are expressed as a result of their inalienable right to freedom of expression and under their own responsibility. The contents included in the summary of this conference are the result of the discussions that took place during the conference organised for this purpose at the Foundation and are the sole responsibility of its authors.