The opportunities of AI in education

In the chapter on the challenges of developing AI in Spanish, we explain both the history of the technology and the basic principles of how it works. We will now explore the different ways in which AI (and LLM language models, such as ChatGPT and others) could transform education in the coming years. For example, AI systems could personalise learning, improve both assessment and attention to learners, and also transform educational resources into accessible materials quickly and cheaply. Traditionally, education has followed a 'lecture' approach, where all students receive the same material from teachers, with one-size-fits-all and little personalised adaptation, regardless of their individual abilities, learning styles or rates of progress. However, thanks to AI, teaching could be tailored to the specific needs of each student, as is the case, for example, in personalised medicine. In this sense, intelligent tutors - AI-based systems that interact with students in real time - could provide detailed explanations and answer personalised questions immediately. Just as ChatGPT can adapt the complexity or tone of its responses, depending on the user's requirements, these intelligent tutors could adjust the difficulty level of the material according to the student's performance, and thus provide personalised feedback and interaction, even suggesting additional resources to reinforce areas where the student may be struggling. In addition, they can make it easier to monitor students even when they are working from home, which is also conducive to improving equity among students, whatever their personal situation and economic status. This personalisation capability could not only improve students' understanding and retention, but also increase their motivation and engagement in learning. Some studies suggest that AI could make education more sustainable, democratising access to all types of learning content and formats from anywhere in the world.

In addition to these intelligent tutors, AI also helps to find content tailored to each student's preferences and needs. Thanks to advanced algorithms and LLMs, the student's progress and interests can be analysed to suggest personalised educational materials. For example, if a student shows a particular interest in the medieval history of Spain, the system can recommend books, articles, videos and activities related to that topic. This personalisation and tailoring of content not only enriches the student's learning experience, but also fosters a passion for learning by connecting studies to personal interests.

AI will also transform the work of teachers. Traditional assessment methods often involve written tests and manual marking, and this can be a slow and error-prone process. In standardised "multiple-choice" tests (which already currently follow automated marking methods) such errors can be difficult to detect. AI would avoid the vast majority of such errors, and could even automate the reading and marking of exams and written assignments. Moreover, thanks to connected systems, corrections and feedback could reach students relatively immediately. Such systems are not only faster, but can also be more accurate, because they eliminate much of the human bias and ensure a fairer and more equitable assessment. LLMs could provide detailed and personalised remediation for each student, highlighting the specific areas where the student needs to improve and, at the same time, providing both strategies and supplementary materials to do so. An analysis by the World Economic Forum also highlights other benefits for teachers: reduced workloads, thanks to AI, could allow teachers to have more time to better serve their students and reduce their professional burnout. Currently, teachers spend less than half of their time directly with students. Having systems that reduce their workload could result in a better teaching experience and increased productivity.

Universal and free access to education (and educational resources) is fundamental to the advancement of a democratic society. And LLMs can play a key role in making education more accessible to all. Advanced language models can translate and adapt educational materials to different languages and cultural contexts quickly and effectively. While some experts predict that the interest (and usefulness) of learning languages will decline, AI opens up a world of possibilities for teachers and students around the world. For example, a student in a rural region of Spain can access an online course at any prestigious university in the United States thanks to machine translation and cultural adaptations. This ability to break down language and cultural barriers is essential to democratising access to education and ensuring that all students have equal opportunities to learn and grow. The website Coursera, one of the world's leading online education companies, announced late last year that it would use AI translation systems to offer many of its classes in 17 different minority languages, including Greek, Indonesian, Kazakh, Ukrainian and others.

These new technologies can also facilitate access to educational resources for students with disabilities, thanks to applications such as screen readers for students with visual impairments (which many digital media have already incorporated, as a complement to the default readers installed on mobile phones and operating systems) and voice recognition solutions for people with motor disabilities. In addition, LLMs can generate adapted versions of educational materials, such as textbooks in Braille or audio descriptions and real-time subtitles, both for multimedia content and for lectures. In this way, we can ensure that all students have access to the same information and can participate in lessons. Several research groups are also working on the development of robots and AI tools to improve the educational experience of students with dyslexia and autism, to complement the work of teachers and social workers. These systems often not only help students, but also learn from them, their gestures, preferences and favourite ways of learning, and can adapt educational content to facilitate progress.

Inclusiveness is not limited to physical disabilities. Thanks to AI applications in education, barriers between learners from diverse socio-economic backgrounds can also be reduced. Learning platforms online provide access to quality education to students all over the world, regardless of their geographic location or financial situation; all that is needed is an internet connection. Personalised recommendation algorithms can help students find the most relevant courses and materials for their needs, to maximise their learning potential. In addition, a number of scholarship and support programmes are beginning to incorporate AI-based systems to identify and locate talented students among disadvantaged communities, using the analysis of academic performance data to identify those with the greatest potential and provide them with the resources and support they need to succeed. These systems can include not only scholarships, but also personalised tutoring, dedicated mentoring and access to additional educational resources.

However, AI can also become a double-edged sword: it could amplify the effect of existing biases, as algorithms are trained from databanks that are often sexist and racist. The models of machine learning are only as good as the training data, so it is important to use them in an educated and critical way to avoid reproducing problems such as those that occurred in the UK in 2020, when university entrance exams were cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic and an algorithm allocated grades to students based on secondary school grades and penalised students from schools in more disadvantaged areas. However, there are also positive examples. Several studies, including one led by the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, have shown that algorithms can analyse student performance and behavioural data to predict who is at high risk of dropping out of school. This information allows educators and administrators to proactively intervene and provide the necessary support to keep students on the path to academic success. It is important to understand how AI works and learn responsible ways to use it, as well as to develop strong regulatory policies to avoid perpetuating bias and maximise the benefits of technology in education.

In addition, AI is transforming the learning experience by making it more interactive and engaging. One of the most innovative aspects of this is gamification, a technique that uses game elements, such as points, rewards and challenges, to make learning more engaging. AI-based education systems can design activities and lessons that incorporate these elements automatically and in a personalised way, to keep learners engaged and motivated. For example, platforms such as Duolingo, a language learning app, already use gamification. Thanks to AI, moreover, these platforms could adapt challenges according to the learner's skill level and ensure that the content is both stimulating and achievable. This not only improves information retention, but also fosters a positive attitude towards learning.

Collaboration is another area where AI is making significant advances. Educational platforms can be upgraded to maximise interaction and cooperation between students and teachers from different parts of the world, thanks to tools such as machine translation and content generation. Algorithms can also improve the behaviour of existing tools such as discussion forums, video conferencing and collaborative workspaces through their abilities to recognise text, respond in an informed way and organise data. AI could, for example, moderate interactions between students and provide live translations and assistance to facilitate the flow of conversation. This not only reduces the workload for teachers (and moderators), but also reduces the workload for students. online), but also enables students to work better collaboratively, regardless of their social or geographical background, and to participate in projects where ideas are shared regardless of language and where they can learn from each other. This not only enriches learning by introducing diverse perspectives, but also prepares students to work in multicultural and international environments in their professional lives. Overall, artificial intelligence is transforming the educational experience, both from the student's and the teacher's point of view. The vast majority of changes are positive developments, such as personalisation of content, universality, collaboration and accessibility. However, some challenges still need to be resolved to ensure democratic and equitable access to AI, especially around regulatory issues. But in any case, beyond the potential problems, education could be transformed into a more diverse, global and inclusive experience. After all, education is a universal fundamental right.

A further step in the digital transformation of education

ChatGPT is already used by the majority of teachers in the K-12 system (5-18 year olds) in the United States, and the practice is growing: in March 2023, 51% of teachers were using ChatGPT, but by July 2023 the percentage had risen to 63%. Of these, 30% used it to plan lessons, another 30% to generate new creative ideas for lessons and 27% to improve their prior knowledge. This is not surprising because 88% of teachers and 79% of students believed in early 2023 that ChatGPT would have a positive impact, and 76% and 65% respectively advocated incorporating it into the educational process. In the UK, 42% of primary and secondary teachers used generative AI to help with homework in November 2023, a significant increase from 17% in April 2023. AI ranks third in the top ten subjects children want to learn in Spain and more than half of parents in Europe are in favour of using AI to assess and improve their children's educational outcomes.[iii]. These figures contrast with the high perception of risk that still accompanies the new technology, due to the lack of caution with which it is being introduced into education. Most teachers say that their schools do not have a guide to generative AI, do nothing to train them, and do not meet the demand from students who want to develop in the kind of jobs that AI will require. In a way, children, parents and teachers are discovering one of the most powerful technological tools in human history... on their own.

Recent regulation, however, provides a very strict framework in this regard. The EU's Artificial Intelligence Act includes in its famous Annex III of "high-risk" activities those aimed at determining a student's access to education and the level of education for which he or she is eligible, as well as those that assess learning outcomes and monitor student behaviour during testing. These use cases are permitted, but require strict risk assessment procedures. According to the European standard, teachers and educational institutions will have considerable responsibility for the appropriate use of AI tools that suggest or make decisions and should not resort to systems that allow the interpretation of a person's emotional state in the context of education. Although less explicit than the European approach, the US Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) allows teachers to use educational software without the permission of their parents or guardians as long as there is a legitimate interest and the sharing of information is limited.

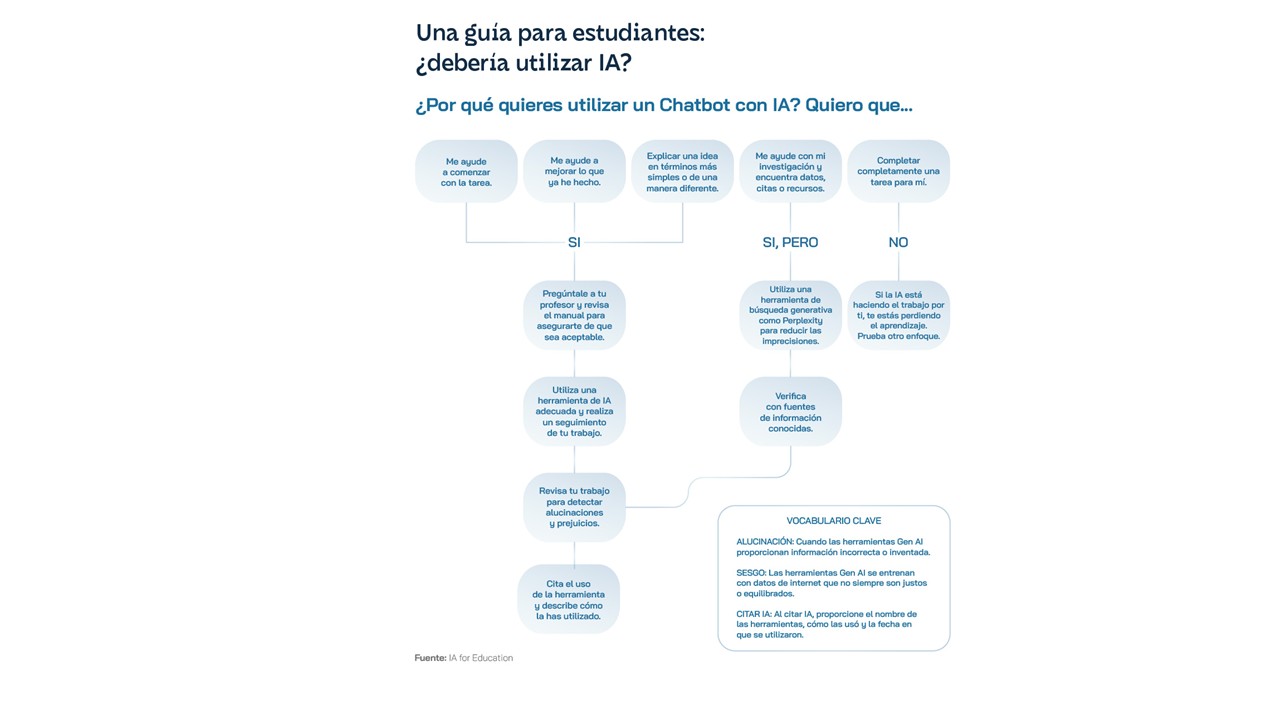

But AI tools can easily exceed these exceptions, particularly among students under 13, depending on whether they are deployed in an open or closed environment and where the data comes from. So, wake-up calls are commonplace. Teachers mostly use generative AI tools, indeed, but almost 50% express unease about the danger of irresponsible use by students, 62% want guidance on how to teach them to use it and 54% call for strategies to identify bad practices. Some of the consequences of implementing the technology are unpredictable: one experiment showed that an AI application based on ChatGPT was harmful to students' performance because, instead of helping, it was more of a distraction. The researchers' conclusion was that the challenge is not simply to add new technology as if it were an end in itself, but to rethink the whole learning process for students and find out how AI can help them, so that it is not just a flashy and seemingly harmless add-on.[viii]. In that vein, the US government considers it key to introduce transparency about AI models, because educators need more than a heads-up, they need to understand how they work. The selection of an AI model can also be a way of limiting an educational institution's learning offer, as there is no such thing as general-purpose AI. He urges, therefore, to proceed with systems thinking. The scope of learning is broader than just the AI component. Indeed, the traditional approach to AI in education is diversifying and increasingly incorporating co-creation processes involving researchers, students, teachers and developers from the perspective of intelligence augmentation rather than substitution, towards hybrid solutions between humans and AI.

The current ability of generative AI tools to generate content that closely resembles human handwriting also poses a significant threat to the fairness and authenticity of academic assessment. One survey found that 26% of K-12 educators had identified at least one student cheating using ChatGPT by 2023. The problem is that if institutions or teachers take an individualistic approach and choose different applications to detect whether their students have availed themselves of generative AI, given that the rate of false accusations is still estimated to be around 15%, values such as inclusivity and educational equity could be affected, to the benefit of dishonest students. AI detection tools can be easily manipulated or circumvented using relatively simple adversarial techniques. The average accuracy of detectors of unmanipulated AI-generated content is 39.5%, but drops to 22% if adversarial techniques are applied, whereas if it has been written by humans the accuracy is 67%.

A survey of Council of Europe member states revealed in 2022 that only 4 out of 23 had policies and regulations in place for the use of AI systems in education. In November 2023, only 4% of North American education districts had a formal, documented policy to regulate the use of AI. About 52% recognised that their teachers were independently incorporating AI into their practice. The Consortium for School Networking and the Council of the Great City Schools sought to alleviate this by jointly publishing a "K-12 Generative AI Readiness Checklist", a questionnaire developed in partnership with Amazon Web Services. TeachAI involved 60 experts, governments and organisations, including Code.org, ETS, the International Society for Technology in Education, Khan Academy and the World Economic Forum, in the development of an "AI Toolkit for Schools". To a lesser extent, countries such as Chile, the Ministry of Education launched in May 2023 a guide to foster active learning with ChatGPT and so have US states such as North Carolina, whose guide calls for a review of EdTech providers implementing generative AI to examine its safety, privacy, reliability and efficacy.

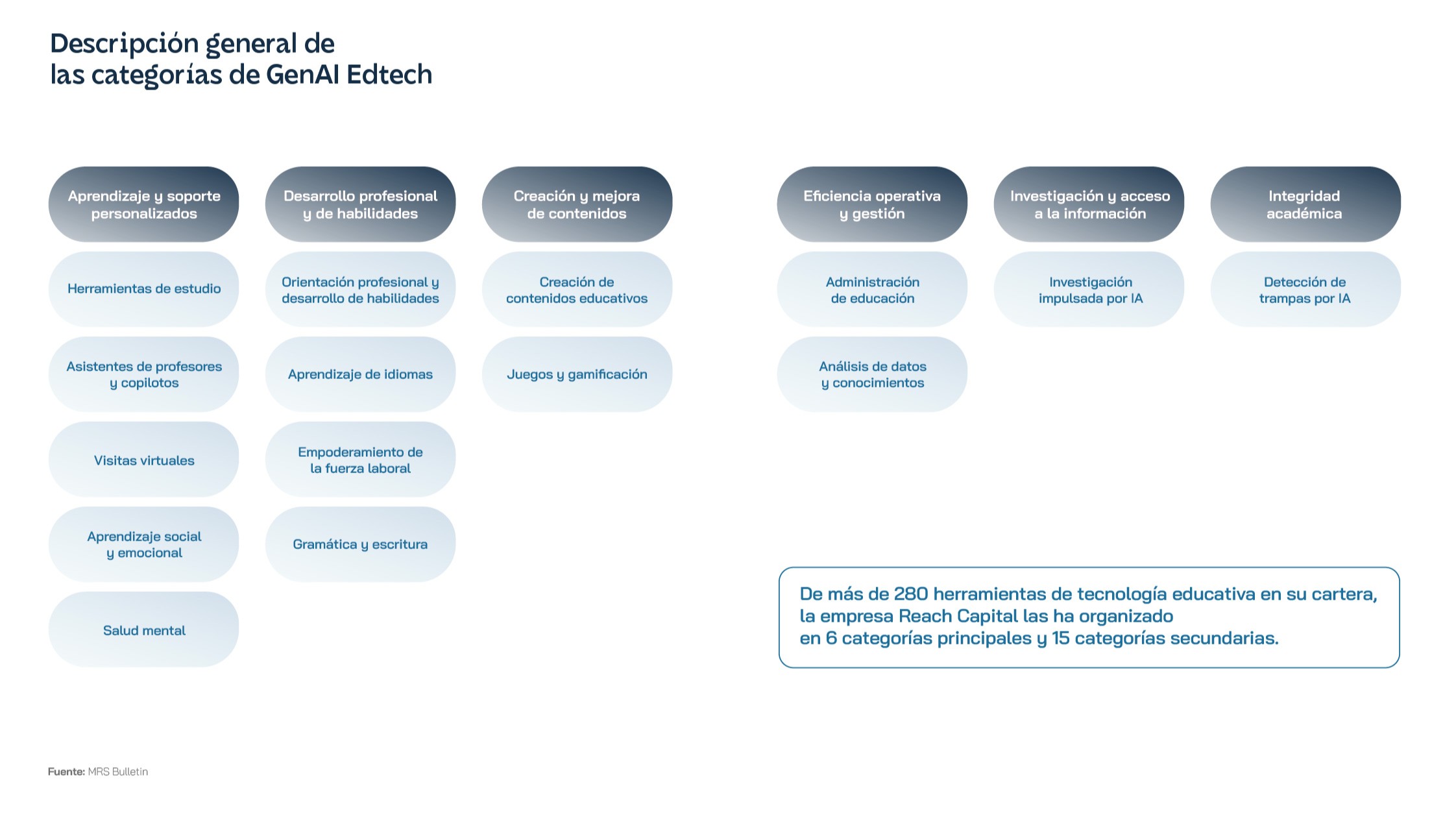

In the face of the slow reaction of educational institutions, the market for AI products is constantly adding new options for teachers, and few of them are thoroughly evaluated. The barriers to entry for creating an AI-based educational startup are extremely low, because it is the tool itself that facilitates its own expansion: generative AI has democratised software development and allows many more people to write it with just a modicum of coding knowledge. If it can be described, it can probably be built, is the current mantra. The playing field is being levelled and almost two-thirds of organisations are already actively exploring AI integration. In that sense, start-ups are taking advantage of the fact that digitalisation has penetrated the education system as well as other areas of the economy and society. From VLE (virtual learning environment) and MOOC (massive online open courses) platforms, to interactive surveys, application and data warehousing, learning analytics and plagiarism detection software, multiple approaches that did not exist two decades ago have become central today. UNESCO states in a report that "good, unbiased evidence on the impact of educational technology is scarce... much of the evidence comes from those trying to sell it".

Demand is not the problem in the new global education market. The current size of AI in it is around $4 billion, but it is expected to grow to $30 billion by 2032 due to its increasing use in higher education and corporate training. Expanding the focus, it is estimated that generative AI could bring $200bn in value to the global education sector by 2025, because retraining and reskilling workers alone could require $16bn in investment, assuming only around 6% of those affected opt in. Paradoxically, almost all countries in Europe are heading towards a teacher shortage scenario, with 25,000 vacancies in Germany by 2025, 30,000 in Portugal by 2030 and 4,000 already in France. The forecast of mass retirements will impact especially on primary schools, with 60% of teachers over 50 years old in Italy, 37% in Germany, 42% in Portugal, 36% in Sweden and 23% in France. And the migration of AI PhDs from academia to industry continues to grow at a rapid pace. It can be defined as a real brain drain: in 2022, 70% joined a tech company and only 20% joined a university, 5.3 percentage points more in just one year.

The demand for AI-based solutions also responds to a clear operational need. Education and learning will be the industries most affected by AI in the next three to five years. In OECD countries, teachers spend on average about half of their weekly time on teaching and the other half, about 17 hours, on organisational and planning activities. In the classroom, only 78% of time is spent on learning activities, while another 13% is used to manage behaviour and 8% on administrative tasks. Teachers can reallocate between 20 and 30% of their time to activities that help improve student learning, and one of the most promising areas in this regard concerns the development of social and emotional skills. Around 3.5 hours are spent on this, and the potential to increase this by reallocating the time saved to other tasks is obvious. It is easy to foresee that the market for teacher support tools will be multi-billion in Europe and the entry of generative AI will bring a new dimension to assessment and question feedback tools, in subjects where correct answers tend to be more factual and prescriptive, as well as to lesson planning and preparation, arguably the most dynamic at present.

In the first half of 2024, there were around 550 AI startups in education in Europe, including some already relevant ones such as Shape Robotics, Iris.Ai, Soapbox Labs, Up Learn and Seervision. Most edtech startups are local and have verticalised solutions aimed at improving communication between teachers and parents or digitising payments in schools. Many will end up being acquired by large companies in search of volume in the real competitive battle for the leadership of school operating systems across Europe. This will be because, although they show differences, schools and colleges end up having very similar core activities across the continent in terms of timetables, class ratios, curricula, pedagogy and administrative functions. It is time for developers of tools that are highly integrated with the rest of the schools' technology, tools that allow teachers to accelerate their tasks with a teaching assistant who knows their local needs. The Austrian company Teachino, with its AI assistant Thenais one of the most interesting in this respect, while others such as the Swiss Taskbase and sAInaptic focus on assessment with b2b systems to align student responses with learning objectives by designing intelligent tutorials and personalised feedback.

Landing these new solutions requires in parallel an adaptation of the ICT infrastructure in schools. Go Student's GoVR project helps children learn languages in a virtual reality experience in which content is translated and generated in real time to make it appear as if the user is talking to a peer in another country. Ferris State University, has developed two AI students, named Ann and Fry, who will participate in classes like any other student, submitting assignments and participating in classroom discussions. Ann and Fry will be able to choose a major and eventually earn their undergraduate degree, if they choose to do so. At the University of Murcia, Vodafone and Samsung have implemented a similar simultaneous translation system, but it has been possible because they have reinforced it with the connectivity power and low latency of 5G and not all educational spaces are ready to make that leap. Outside the developed world, 244 million children are out of school, and AI-based solutions could be an interesting avenue for literacy if shared, low-cost smartphones capable of working in the classroom can be leveraged. offline.

UNICEF has revealed that a third of the digital learning platforms created during the COVID-19 pandemic are no longer maintained or updated and the vast majority lack interactive content. The European Commission has set a target that, by 2030, the proportion of eighth graders with low achievement in computer and information literacy should be less than 15%. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, only 37.51 PT3T of lower secondary teachers in the EU felt they were well or very well prepared to use digital technologies in teaching. Member States have significant support available for investment in education and skills through the Resilience and Recovery Mechanism, amounting to over €70 billion, but nothing is guaranteed - they have to compete for this funding with many other areas of the economy and society. Among the open initiatives to offer new options to the educational ecosystem, EIT Digital and 12 other leading European organisations in education, research and technology have launched the EMAI4EU project to train professionals in the field of emotional artificial intelligence. The Spanish Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and Tech Valley Management are participating.

The transformative power of AI in education also applies to its extraordinary abilities to extract knowledge from data. The Khan Lab School in Mountain View (California, US) and the New York City Department of Education use AI to predict student dropout rates and student attendance and guidance based on this information. The University of Pittsburgh, meanwhile, uses technology to analyse student performance on standardised assessments and provide teachers with resources and support to help them achieve better results. A recent study at Stanford University has shown that brief tutoring, as little as 10 minutes a day, can significantly improve the literacy skills of young students.[xl]. The global private tutoring market could grow from $57.92 billion in 2023 to $105.98 billion in 2030, but without AI solutions to help democratise access, its benefits will be restricted to those who can afford it.

The tasks that are most likely to benefit from the augmentation potential of LLMs tend to emphasise analytical and problem-solving skills, but AI in education not only helps students improve their computational thinking skills in the classroom. It can also create new ways to connect with their local environments, enable them to think critically about ecological problems and help them find realistic solutions.[xlii]. High school students in Maine analysed the capabilities of an AI bird feeder before diving into the analysis of historical data on puffins living on the coast.

Spanish classrooms demand more AI

Spain has some prominent names of its own in the so-called Edtech revolution. Luis Pérez-Breva, director of the MIT School of Business Team Innovation, is a member of the faculty of the MIT School of Business Innovation. Interestingly, the main technology platform on which this initiative is based is also Spanish. It is called Global Alumni, founded by Pablo Rivas and headquartered in Madrid. It manages registrations, technology and participant attendance. It opened the world's largest immersive telepresence room in Boston and runs the University of Chicago's online programmes. MIT Professional Education offers current short programmes, micro-masters designed in many cases in the middle of the last decade, which attract more than 1,500 students a year from around the world. Individuals will be trained in short content, focused on developing a specific skill, demonstrate competence through an assessment and be issued a "credential". However, despite pioneers like Rivas and Pérez-Breva, one of the most vexing questions of the future concerns the ability of our academic centres of excellence to cope with the tsunami of the EdTech revolution.

For the challenge of harnessing the time that artificial intelligence frees up for teachers, initiatives such as EMAI4EU have been launched.[i] a four-year project to train professionals in the field of emotional artificial intelligence. Along with EIT Digital, the consortium includes the Spanish Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Saturno Labs and Tech Valley Management. The other members are Université Côte d'Azur, Université de Rennes, Eurecom and LudoTIC (France); University of Trento, Polytechnic University of Milan and Medispa Srl (Italy); University of Turku (Finland); and Eötvös Loránd University (Hungary). EMAI4EU's flagship programme focuses on Artificial Intelligence of Emotions and aims to help machines interpret and respond appropriately to human emotions.

The first Observatory of the Impact of Technology in the Professions prepared by the Alfonso X el Sabio University, in which more than 2,000 students and almost 400 teachers and professionals participated, reveals that three out of four students under 25 years of age in Spain use generative AI, while the average use among professionals stands at 36%, with special incidence in the 35-45 age group (44%). When children in Spain are asked which subjects they want to learn about, technology development in artificial intelligence, virtual reality and augmented reality comes first, ahead of life skills. Next comes artificial intelligence in general, followed by robotics, sustainability and climate education, coding and programming, finance, wellbeing and mental health, current affairs and creative arts. And it's not just children who are excited about the potential of AI: more than half of parents in Europe are in favour of its use) to assess and improve their children's educational outcomes, and half think that being taught in a virtual classroom (using virtual reality) will improve the learning experience.

Genially, Odilo, Smile & Learn, ABA English, Lingokids, Ironhack and Fiction Express are some of the Spanish edtech companies that have attracted the most investment in recent years. It is estimated that the sector has around 250 companies, ahead of Germany and very close to France, with around a hundred more. In mid-2022, Odilo closed the largest financing round ever for an edtech in Spain, for 60 million euros. It defines itself as a platform similar to Netflix or Spotify, which intelligently and personally selects from the largest digital educational catalogue in the world, with titles and learning experiences from more than 6,300 of the best providers of ebooks, courses, podcasts, videos, magazines, press, educational resources, summaries, films and educational apps in 43 different languages. Another company with a long history of innovation in our country is Smartick, an online learning method with artificial intelligence that manages to adapt in real time to the pace and learning capacity of each student.