La Fundación Rafael del Pino organizó la Conferencia Magistral «La crisis del capitalismo democrático» impartida por Martin Wolf. Martin Wolf es editor asociado de Economía y comentarista económico jefe de Financial Times. Está considerado uno de los economistas más reconocidos de la escena internacional. Las revistas Prospect o Foreign Policy lo describen como «el periodista financiero más influyente de la «Anglosphere» y personalidades como Kenneth Rogoff o Lawrence Summers lo consideran «el principal escritor financiero y económico del mundo». Ha sido profesor visitante en las universidades de Oxford y Nottingham, miembro del Foro Económico Mundial en Davos y de la Comisión Vickers del Reino Unido, así como Distinguished Visiting Fellow for International Economics del Council on Foreign Relations. Además, es doctor Honoris Causa por las universidades de Lovaina, Londres, Nottingham y la London School of Economics. Martin Wolf ha puesto a disposición de todos los interesados su intervención, que pueden leer a continuación.

La Fundación Rafael del Pino organizó la Conferencia Magistral «La crisis del capitalismo democrático» impartida por Martin Wolf. Martin Wolf es editor asociado de Economía y comentarista económico jefe de Financial Times. Está considerado uno de los economistas más reconocidos de la escena internacional. Las revistas Prospect o Foreign Policy lo describen como «el periodista financiero más influyente de la «Anglosphere» y personalidades como Kenneth Rogoff o Lawrence Summers lo consideran «el principal escritor financiero y económico del mundo». Ha sido profesor visitante en las universidades de Oxford y Nottingham, miembro del Foro Económico Mundial en Davos y de la Comisión Vickers del Reino Unido, así como Distinguished Visiting Fellow for International Economics del Council on Foreign Relations. Además, es doctor Honoris Causa por las universidades de Lovaina, Londres, Nottingham y la London School of Economics. Martin Wolf ha puesto a disposición de todos los interesados su intervención, que pueden leer a continuación.

“It is clear then that the best partnership in a state is the one which operates through the middle people, and also that those states in which the middle element is large, and stronger if possible than the other two together, or at any rate stronger than either of them alone, have every chance of having a well-run [democratic]constitution.” Aristotle, Politics

“μηδὲν ἄγαν” (Nothing in excess.)

From the Temple of Apollo at Delphi

The democratic recession

In a liberal democracy — a democracy characterised by individual civil rights, the rule of law, and respect for both the rights of the losers and the legitimacy of the winners — fair elections determine who holds power.

Attempts by a head of government and state to subvert the election or overturn the vote are treason. Yet that is what Donald Trump attempted to do both before and after the last presidential elections.

He failed. Decent and brave people ensured that. But to this day, despite the mid-terms, Trump continues to hold the loyalty of his party’s base and, forced or not, of nearly all its presidential candidates, too.

Meanwhile, conservative stalwarts, such as Liz Cheney, were defenestrated. Her crime? Stating that Trump’s Big Lie that the outcome of the election was a lie is a Big Lie.

The Republican party — one of the two main parties in the world’s foremost democracy — is no longer committed to the most fundamental of all democratic norms: fair and free elections.

Yet, how can a democracy survive if people think the only thing that matters is winning? Democracy is founded on moral values: we are all citizens; we govern through debate; and we argue honestly. With these values gone, what is left but violence?

Trump is, alas, far from alone. Freedom in the World 2021, from the independent US watchdog, Freedom House, published in February, reported a 16th consecutive year of decline in the health of liberal democracy. The “democratic recession” noted by Larry Diamond of Stanford and the Hoover Institution more than one and a half decades ago is close to a “democratic depression”.

This decline occurred in all regions of the world, notably in the fragile democracies that emerged after the Cold War. But, most significantly, it is also observable in core Western democracies including the US, the most important of all democracies, indeed the country that saved democracy in the 20th century.

How democratic capitalism was born

According to the Polity IV database, there were no democracies two centuries ago. Even where republican institutions did exist, the franchise was highly restricted, on the grounds of sex, race, and wealth.

Then in the 19th century, franchises were widened and universal suffrage democracy emerged and spread in fits and starts to cover half of the world’s countries after 1990, before declining once again. This did not happen everywhere. But it happened in enough important countries to change the world.

Why did this happen? It is, after all, rather extraordinary that democratic principles were accepted by so many countries.

The normal way to structure the economies and politics of complex societies has been for power to marry wealth and wealth to marry power: the most powerful people in society were the richest and vice versa. Absolute monarchs effectively owned everything.

Why did this revolutionary change towards democracy occur? The answer lies in the emergence of a marriage between two very different partners: a liberal economy and a democratic polity. Market capitalism and democracy are, I argue, “complementary opposites”.

The market economy and universal suffrage democracy both reject ascribed hereditary status. They embrace the idea that people are entitled to decide important things for themselves.

Market capitalism rests on ideals of free labor, individual effort, reward for merit, and the rule of law. Democracy rests on ideals of free discussion and debate among citizens when making those laws.

Historically, the market economy also brought urbanisation, demand for a more educated workforce, the newly organised working class, as well as opportunities for “positive sum” politics.

Democracies rest on the existence of an economically independent citizenry. That was Aristotle’s point. A fully socialist society is inevitably a dictatorship, since the ownership of productive assets is vested entirely in the state. In the absence of co-ordination through competitive markets, that state is then responsible for the allocation of those valuable resources. It has too much power

Markets protect democratic politics from such an excessive concentration of power, but democratic politics also protect markets from an excessive concentration of wealth.

This then is how the market economy and liberal democracy are complementary.

Yet they are also opposites. Capitalism is inherently cosmopolitan; the democratic state is territorial. The market is the domain of “exit”; democracy is the domain of “voice”. The market economy is inegalitarian (one dollar, one vote); democracy is egalitarian (one person, one vote).

Tensions between capitalism and democracy will inevitably emerge.

If the economy fails to serve the interests of the majority, the sense of shared citizenship will fray and populist demagogues will emerge. Such populism is not necessarily lethal for democracy, so long as it takes the form of a justified (even fruitful) hostility to elites. But often it transforms into hostility to pluralism itself, which is an essential element in any democracy.

In sum, democracy and the market are married to each other. But it is a difficult marriage, as so many are.

Democracy is then transformed into a “plebiscitary dictatorship” and ultimately a dictatorship, tout court, in which the dictator insists that “le peuple, c’est moi”. Alternatively, the concentration of wealth can lead to plutocracy as wealth is once again transmuted into power. Indeed, it is quite likely to have predatory autocracy and corrupt plutocracy in uneasy tension. That was the governing system of the Roman Empire.

Today’s unhappy high-income democracies

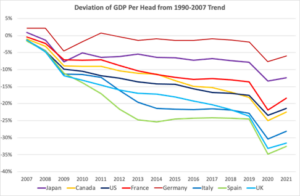

Large rises in inequality and the deteriorating prospects of the old “respectable” working and middle classes in core democracies have been eroding the foundations of democracy.

The fear of downward mobility has created “status anxiety” and political cynicism. These have then been diverted by right-wing propagandists into cultural and racial resentments, especially in ethnically diverse societies.

This is not new. It has long been the foundation of the political culture of the American South. Mutatis mutandis, this was the foundation of interwar European fascism, too.

Those resentments have been greatly aggravated by the emergence of a large and discontented class of university-educated “clerics” dedicated to a “progressive” cultural and racial politics. This identity army of the left then clashes with (and motivates) the majoritarian (“silent majority”) identity army of the right.

The emergence of the “new media” have facilitated all these trends. But they have not created them.

A big question is what has happened to create this “status anxiety”, especially in people who did not go to college.

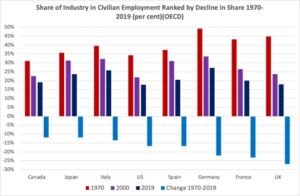

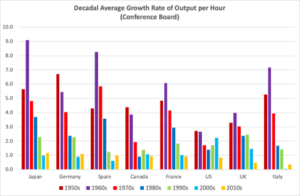

In the long run, the important phenomena have been economic: deindustrialisation, rising inequality, and falling productivity growth.

An intriguing fact is that the US and UK are the most unequal of the big high-income democracies and they have also had some of the potent right-wing populist politics. Is that an accident?

As Raghuram Rajan argued, easy credit papered over these trends. But that blew up in the financial crisis. The scale and visibility of the crisis and subsequent rescue of the banks and bankers convinced many that elites were both corrupt and incompetent.

That is why the Republican establishment became so ripe for a populist take-over. But in truth what happened discredited the establishment in both parties, as it did in the UK over Brexit.

The shift towards skill-intensive sectors and technologies, de-industrialisation of the labour force, globalisation and the rise of China were the product of powerful underlying economic forces.

Yet there is also substantial evidence of the emergence of “rentier” capitalism, with declining competition, rising monopoly, and unbridled self-seeking by corporate executives.

Furthermore, the role of money in politics, especially in the US, has eroded the tax base and the effectiveness of regulation.

Democratic capitalism in today’s world

Branko Milanovic argues that capitalism is “alone”: it has won.

Yet what sort of capitalism has won? Is it what Milanovic calls “liberal capitalism” and I would call “democratic capitalism” or is it to what he calls “political capitalism” and I would call “authoritarian capitalism”?

There are in fact two forms of authoritarian capitalism.

The most common version derives from a hostile takeover of democracies. The would-be autocrat eats out democracy from within. Usually, he starts as a populist demagogue. Features of such regimes include a narrow circle of trusted servants, promotion of members of the family, and “power ministries” who are personally loyal to the leader. Plutocrats may find it necessary to support the gangster in charge. Ultimately, however, they survive only as his cronies.

The other challenge is “bureaucratic authoritarian capitalism”: the Chinese system. A communist bureaucracy operating a capitalist economy can be self-disciplined, long-sighted, technocratic, and rational.

Even so, bureaucratic capitalism also suffers from the vices of authoritarianism, especially the tendency towards corruption, and crony capitalism. These failings damage both the economy and political legitimacy.

Bureaucratic authoritarian capitalism is a significant challenger to Western democratic capitalism. Yet, we must not despair.

Autocracies are bad systems: they do not have a structure of accountability; they do not have an open debate; they cannot ensure the peaceful transfer of power; and they tend towards unbridled cronyism and corruption. Indeed, corruption too often becomes the system.

Moreover, liberal democracy has come through many challenges over the past century.

More fundamentally, it is the right system. It rests on the magnificent belief in the right of people to make up their own minds and lead lives they choose within societies whose joint decisions are taken with the active consent of the governed.

Renewing democratic capitalism

The renewal of democracy and capitalism must be animated by a simple but powerful idea: that of shared citizenship.

If democracy is to work, we cannot think only as consumers, workers, business owners, savers, or investors.

We must think as citizens.

Today, citizenship must have three aspects: loyalty to democratic political and legal institutions and the values of open debate and mutual tolerance that underpin them; concern for the ability of fellow citizens to live a fulfilled life; and the desire to create an economy that allows all citizens hope of a better future.

Conclusion

The world has changed too profoundly for nostalgia to be a sane response. Be one on the right or the left going back to the past is a fantasy.

Yet some things remain the same. Human beings must act collectively as well as individually. Acting together, within a democracy, means acting and thinking as citizens. If we do not do so, democracy will fail.

The UK had Boris Johnson and then Liz Truss as prime ministers in succession. One was a fraud; the other was a fanatic. But they were got rid of, peacefully. Contrast this with the fate of Vladimir Putin or Xi Jinping. Both are brutal dictators, and both are also manifestly incompetent. And is there any way to ensure that autocrats will be decent, self-restrained people? None. Is there any way of getting rid of them? None, short of violence.

That is the difference.

It is the difference between rule by consent and rule by coercion.

It is the duty of all of us to ensure that our hard-won democracies do not fail.

Acceda a la conferencia completa